Introduction

In today’s interconnected world, every digital interaction you have, be it browsing a website, watching an online show, ordering food online, playing an online video game, or sending a simple mail, you most probably interacting with a system that is built following the client-server architecture. This fundamental computing model has shaped how developers build, deploy, and scale applications for decades. Therefore, understanding it deeply is essential for anyone working in technology today, especially self-taught developers who need a solid foundation in system design to put them at par with industry standards.

In this article, we walk through the building blocks to the sophisticated metal to cloud server infrastructure in the client-server architecture. This architecture outlines how user devices(clients), communicate with more advanced computers(servers) over the internet to deliver resources and services, render page content, or fetch streaming data, and deliver services to be consumed by these clients in a smooth and fast way.

In this first part of the series, we will cover;

- What the client-server architecture is (basic client-server model)

- How client - server communication actually happens

- State management

- Different types of client-server models

- Server infrastructure

I also acknowledge that the topics I will touch on are very wide and therefore some will be shallow otherwise the article would be very long. But worry not, later on I will dig deep into most topics with code examples and real world use cases.

The Foundation - Basic Client-Server Model

This is a computing model in which a centralized server (powerful machine) hosts, manages, and delivers, data, resources, or services to multiple clients (users or devices) for consumption over a network or an internet connection.

This communication usually starts by the client requesting for some data from the server which then processes the request and sends data back to the client via a protocol. It is important noting that a server can server multiple clients at the same time, but the clients cannot communicate to each other directly.

Key components of the architecture

Some main vocabulary for components and connectors include;

- Client: a piece of software or a device that takes input and sends request to the server (web browser, mobile app, desktop application, or automated crawler)

- Server: an advanced machine that receives client requests, manages resources, and delivers the requested data or services back to the client.

- Load Balancer: is responsible for distributing incoming network traffick across a group of servers to optimize resource usage and ensure seamless user experience.

- Network Layer and Protocols: the communication medium (the internet) that facilitate client-server data exchange

Overview of How the Client-Server architecture works

At its core, the client-server interaction follows a simple pattern that repeats billions of times daily across the internet. Here is where we explain how your browser knows what to show you when you enter a URL, or how your Netflix app pulls movie recommendations for you. This narrows down to how clients and servers communicate.

The client initiates the communication through a request. An action like a click on a button, or opening the netflix app triggers a request to the server to perform a specific action such as data retrieval, resource creation, or an information update.

The request contains a bunch of stuff that we’ll look at in detail when we look at networking fundamentals. The request travels over the network from the local network (your WiFi or cellular connection) all through to the server.

The server receives and processes this request. This phase involves validating the request format and permissions and then performance of the necessary business logic which may involve retrieval and or manipulation of data. Th server then formats the response appropriately.

The Server sends back a response which contains a status code indicating success or failure of the request, requested data or error information, metadata about the response, and instructions for caching or further actions. Finally, the client receives and renders the response on the screen for consumption.

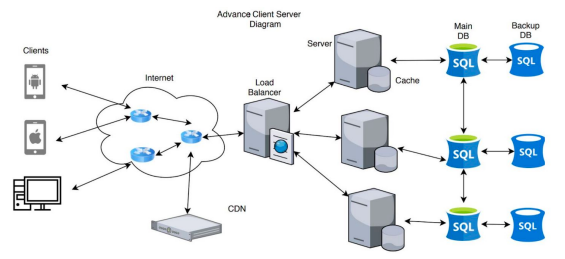

In a real-world advanced system, a typical topological data flow goes as follows (refer to the image above);

- Client sends a request to the server

- Load balancer routes the request to the appropriate server

- Server processes the request during which it queries the database for some data

- The Database returns the queried data to the server

- The server processes this data and sends it back to the client

- The process repeats

Understanding Different Client Types

Not all clients are created and behave equally. Each type has unique characteristics that influence their interactions with servers.

Web Browsers: The Universal Client

These are perhaps the most versatile clients. They are human-driven, where a user clicks, types, and navigates. They are able to maintain login status and user preferences. They also have the capability to handle HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and multimedia. They can also store resources locally for performance and better user experience.

Mobile Applications: The Optimized Client

These are purpose-built clients with specific constraints that are OS specific, can function when network is unavailable, and can receive server-initiated messages. For example, a weather app might cache the current forecast locally, request updates only when opened, and receive push notifications for severe weather alerts.

Web Crawlers: The Automated Client

Crawlers are programmatic clients that operate without human intervention. They can make thousands of requests per minute, follow links and patterns methodically, and parse responses for specific information. Google’s web crawler is an example that systematically visits websites, following links and indexing content to power search results.

Separation of Concerns: Why It Matters

The client-server model enforces a crucial architectural principle: separation of concerns. This isn’t just theoretical—it has practical implications for how we build and maintain systems.

Client Responsibilities

The client has the following responsibilities;

- Offers user interface and ensures experience. The clients handle how information is presented and interactions are handled when sending a request, or when consuming a server response.

- Validates user inputs. Clients offer basic checks before sending requests. These include data types, required form fields, textual data length, and patterns such as ensuring inputs are “email-like”.

- Local state management. Clients, for example the browser have local and session storage utilities that can be used for state management in web applications.

- Network error handling. Clients also know how to respond when servers are unavailable.

Server Responsibilities

- Handling business logic: The server has the core rules and processes of your application that handles requests.

- Data persistence: Servers can store and retrieve information reliably, either acting as databases themselves or communicating with external database servers.

- Security enforcement: They ensure authentication, authorization, and data protection.

- Resource management: Depending on whatever architecture, servers have the responsibility of handling concurrent requests efficiently.

Benefits of This Separation

Independent evolution

This means that clients and servers can be updated separately. One side can be modified without disrupting the other side. It also means that we can rely on a single server when we use multiple clients; iOS apps, web browsers, and desktop applications can all use the same server. Additionally, each server can be optimized for its specific role. It also means that the problems in the client don’t crash the server and vice versa.

Independent Scalability

It gives us the ability to scale both sides independently based on demand, for example upgrading server resources without changing server applications.

It enhances security

This model enables us to strictly handle sensitive business logic and data validation on the server, far away from client-side manipulation. Clients only receiving what they need to render, which reduces the attack surface.

Patterns used in Client - Server Communication

The client-server architecture applies certain fundamental communication patterns to facilitate interactions between clients and servers. While request-response is the foundation in the client-server architecture, modern applications use several communication patterns to facilitate this.

They include;

Request-Response Pattern

Is the most common communication pattern in the client-server architecture. In this pattern, the client initiates the communication when they send a request to the server. The server receives, processes and sends back a response.

This pattern is synchronous, as the client typically waits for the response before sending another request. An example here is an HTTP request, where you request a particular page, and your browser requests it from the web server.

This pattern is often suitable for simple operations, critical data, and user-initiated actions.

Polling Pattern

In this pattern, the client periodically sends requests asking if the server has any updates. Although this pattern is simple to implement because no special server infrastructure is needed, is can be resource intensive since it creates unnecessary network traffic.

Long Polling

Long polling is an improvement over regular polling involving extended waits where a client sends a request, and the server holds it open until new data is available thereby reducing unnecessary requests They are faster that regular polling with minimal resource usage.

Push Notifications

In this communication pattern, the server is the one to initiate communication with the client ie, it is a server-driven pattern. It requires persistent communication, and the client must maintain a connection or register for notifications. This is more efficient since the two only communicates when necessary.

Use cases of this pattern include mobile app notifications and server-sent events.

Publish-Subscribe (PubSub)

This is a decoupled communication pattern that is topic-based, and uses an intermediary between the clients and server (message broker). Clients subscribe to specific topics and channels.

Phoenix has PubSub built right in. Take an example of a radio station, where one person (radio) broadcasts a message and many people listen.

Here is an example of how you would use phoenix PubSub.

# Someone publishes a message (like broadcasting on a radio station)

Phoenix.PubSub.broadcast(

MyApp.PubSub,

"room:lobby", # The "channel" or "topic"

{:new_message, "Hello!"}

)

# Many people can subscribe and listen

Phoenix.PubSub.subscribe(MyApp.PubSub, "room:lobby")

# When a message comes, everyone who subscribed receives it

def handle_info({:new_message, text}, socket) do

# Do something with the message

end

Remote Procedure Call (RPC)

This pattern makes remote calls look like local function calls, and is a synchronous pattern where a client waits for a remote function to complete execution.

# On one Elixir node, call a function on another node

:rpc.call(

:"app@other_server",

MyModule,

:some_function,

[arg1, arg2]

)

Examples include gRPC and XML-RPC

WebSocket Pattern

This is a full-duplex bidirectional communication pattern which involves a persistent or a single long-lived connection. It is real time since both client and server can send data anytime.

It’s like a phone call that stays open. Both sides can talk anytime without hanging up and calling back.

# Client connects (JavaScript)

let channel = socket.channel("room:lobby")

channel.join()

# Client sends message

channel.push("new_message", {body: "Hello!"})

# Server handles it

def handle_in("new_message", %{"body" => body}, socket) do

# Process and maybe broadcast to everyone

broadcast(socket, "new_message", %{body: body})

{:reply, :ok, socket}

end

# Server can push to client anytime

push(socket, "notification", %{text: "Someone joined"})

This if very efficient for real-time gaming and collaborative editing tools.

Message Queue Pattern

This involves asynchronous communication through queues. In this pattern, the sender and receiver do not have to be online simultaneously since messages persist until processed. Examples include RabbitMQ, and Apache Kafka.

Phoenix doesn’t have this built-in, but Oban is the go-to library. t’s like leaving a note for someone to do later. Even if they’re not around now, they’ll get it when they’re back.

# Create a job - it goes into a queue

%{email: "user@example.com", type: "welcome"}

|> MyApp.SendEmailWorker.new()

|> Oban.insert()

# Worker processes it (could be seconds or hours later)

defmodule MyApp.SendEmailWorker do

use Oban.Worker

def perform(%{args: %{"email" => email, "type" => type}}) do

# Send the email

MyApp.Mailer.send_welcome_email(email)

:ok

end

end

State Management in the Client-Server Architecture

This is about where and how you store information as users interact with your application. It is one of the trickiest aspects of client-server architecture. State is just data that changes over time, but not all data is state.

In an app you might want ot check;

- Is a user logged in?

- What items are in the shopping cart?

- Which page are you viewing?

- Form inputs you’ve filled out

- Whether a dropdown is open or closed

Application state can live in three places.

- Client-Side State (Browser/App)

- Server-Side State (Backend)

- Cache State

- Session State

Client-Side State

This is data stored on the user’s device, and we have different types.

UI State (Component State)

This is transient data whose effect is only seen on the presentation layer. It involves temporary, visual stuff such as dropdown open/closed, modal visible, form input values, scroll positions, loading spinners that doesn’t need to persist beyond the current view. This data is lost when you refresh the page.

If you have interacted with LiveView, this can be achieved using Javascript hooks, but can also be handled server-side.

# Client-side UI state using JS Hooks

defmodule MyAppWeb.UserLive do

use MyAppWeb, :live_view

def mount(_params, _session, socket) do

{:ok, assign(socket, users: list_users())}

end

def render(assigns) do

~H"""

<div id="user-dropdown" phx-hook="Dropdown">

<button phx-click={JS.toggle(to: "#dropdown-menu")}>

Options

</button>

<ul id="dropdown-menu" class="hidden">

<li>Edit</li>

<li>Delete</li>

</ul>

</div>

"""

end

end

And then in the JavaScript hook;

// assets/js/hooks.js

let Hooks = {}

Hooks.Dropdown = {

mounted() {

this.isOpen = false

this.el.querySelector('button').addEventListener('click', () => {

this.isOpen = !this.isOpen

// State lives purely in JavaScript

console.log('Dropdown state:', this.isOpen)

})

}

}

export default Hooks

Phoenix LiveView gives you the ability to manage this server-side, especially when you need consistency.

defmodule MyAppWeb.ModalLive do

use MyAppWeb, :live_view

def mount(_params, _session, socket) do

{:ok, assign(socket, modal_open: false, selected_item: nil)}

end

def handle_event("open_modal", %{"item_id" => id}, socket) do

# UI state stored on server for consistency

{:noreply, assign(socket, modal_open: true, selected_item: id)}

end

def handle_event("close_modal", _, socket) do

{:noreply, assign(socket, modal_open: false, selected_item: nil)}

end

def render(assigns) do

~H"""

<div>

<button phx-click="open_modal" phx-value-item_id="123">

Open Modal

</button>

<%= if @modal_open do %>

<div class="modal">

<p>Item: <%= @selected_item %></p>

<button phx-click="close_modal">Close</button>

</div>

<% end %>

</div>

"""

end

end

Server-Side State / Application State (Business Logic State)

This is client-side data state that represents application data and business logic that is typically fetched from or synchronized with the server. Examples of this can be a current user’s shopping cart, search results, form data before submission, etc. In LiveView, application state primarily lives on the server in the socket assigns.

Data stored on the server (database, memory, files). The “source of truth” - authoritative data:

Client Server

| |

|--Request (with auth token)--->|

| | (Check token, fetch data)

|<--------Response--------------|

| |

|--Another request (token)----->|

| | (Check token again - no memory of previous request)

|<--------Response--------------|

If you an elixir developer, you will realize that phoenix framework inverts the traditional client-server state management paradigm by keeping most application state on the server while maintaining a stateful WebSocket connection.

Here is an example showing how state can be stored permanently on the database in a phoenix application. MyAppPosts is a context that has functions that help perform CRUD operations on the database by calling Ecto functions under the hood. They hold the business logic and talk to databases.

# Store permanently

MyAppPosts.create(%{title: "Hello", body: "World"})

# Fetch when needed

posts = MyAppPosts.list_posts()

Server-side state in Phoenix LiveView is remarkably rich because LiveView maintains a stateful process for each connected client.

Cache State

Cashing generally means having a temporary store to data fetched from the database to avoid making unnecessary calls to the databases. This helps making an application faster and helps reduce database load.

In the Elixir/Erlang realm, you have different ways of achieving this. As with most topics, this is also very large and we will look into it deeply in future but here are a few common cashing options in phoenix. They include cachex, erlang term storage (ETS), mnesia and Redis. We will look into these in detail in a different blog.

Session State

Session state bridges individual requests and maintains user identity across connections Data about a specific user’s connection/session:

What user is logged in on this connection Their permissions/roles Temporary workflow data Lives on the server but specific to one user’s session

For authentication across regular requests:

# Store in session when user logs in

conn

|> put_session(:user_id, user.id)

|> put_session(:role, "admin")

# Later requests can access it

def index(conn, _params) do

user_id = get_session(conn, :user_id)

# You know who this is!

end

Here is what the flow would look like.

Client Server (with session storage)

| |

|--Login----------------------->|

| | (Creates session, stores "user123 logged in")

|<--Session ID (cookie)---------|

| |

|--Request (session cookie)---->|

| | (Looks up session: "Oh, this is user123")

|<--------Response--------------|

Types of Client-Server Architectures

Client-Server Architectures are categorized based on the number of layers (tiers) involved in data processing and delivery.

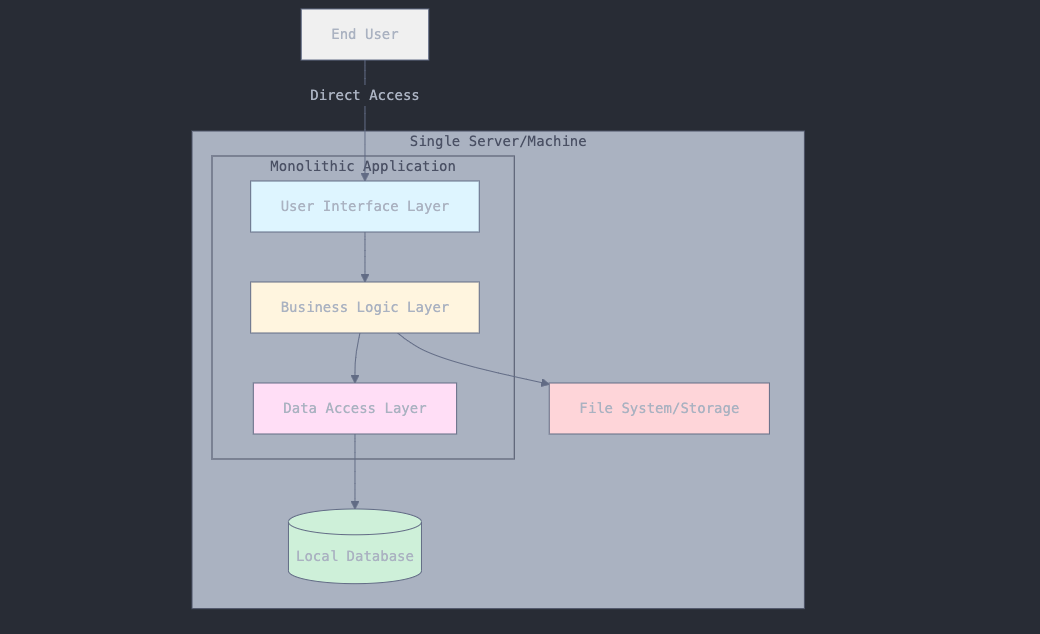

1-Tier Architecture/Monolithic Model

Is where everything from the user interface, to the business logic, to the storage of data resides in a single layer. In other words, all operations are handled by the same machine or within the same application.

Examples include:

- Microsoft Excel

- Personal finance tools that store and compute everything locally

2-Tier Architecture

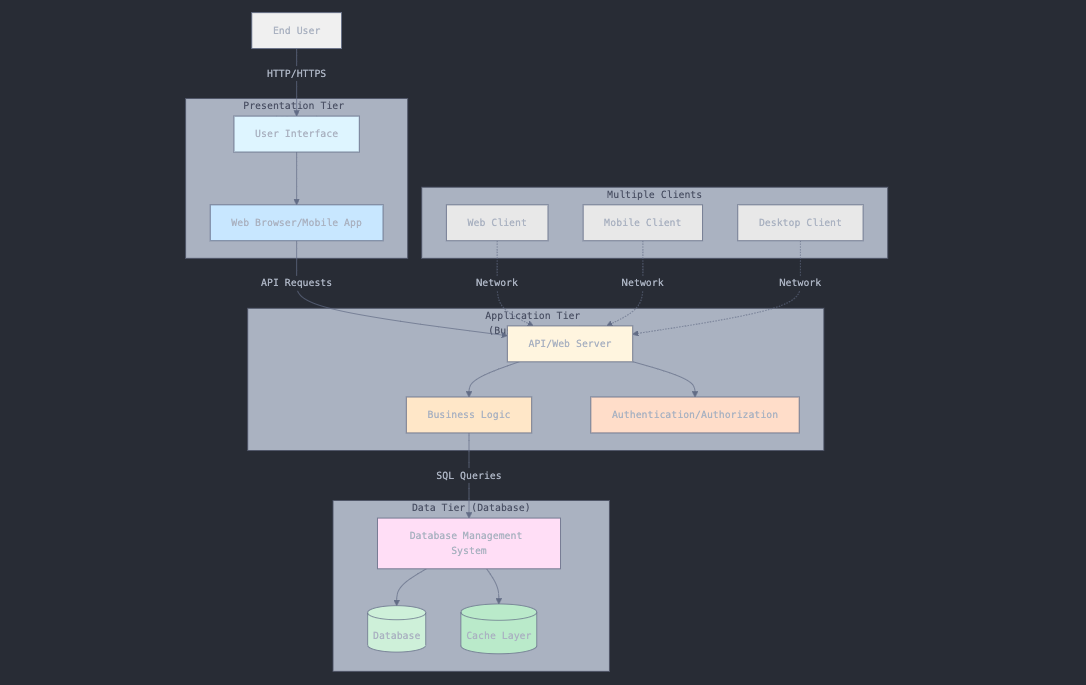

Splits the system into two parts;

- The Client; handles the user interface

- The Server; handles the business logic and data storage

Here, clients communicate directly with the server, sending requests and receiving responses. The server runs the logic, interacts with the database, and returns responses to the client. An example here would be

3-Tier Architecture

It introduces a dedicated application layer (the business logic layer) between the client and the server.

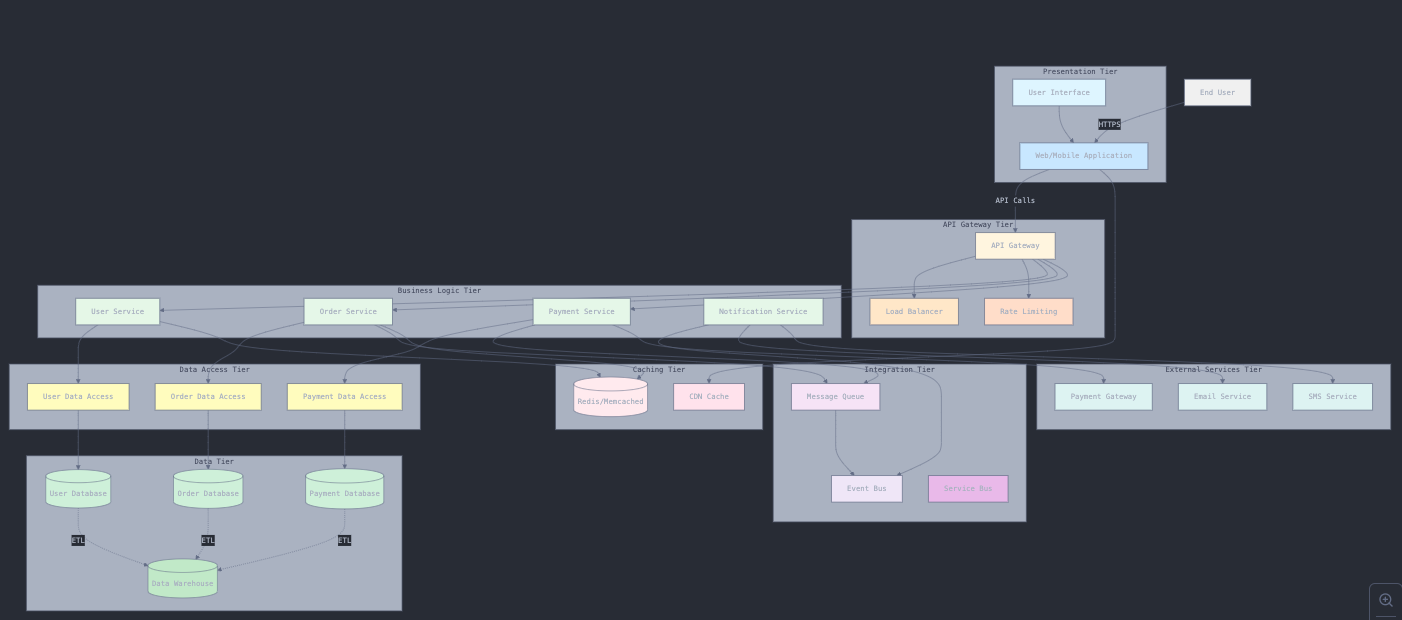

N-Tier Architecture

Builds on the 3-tier model by adding specialized layers for specific responsibilities such as cashing, load balancing, authentication, analytics, and API gateways. Common layers in this model include:

- Client: User-interface or the front-end application

- Presentation layer: manages the user interface and the presentation logic

- Application layer: handles business logic and rules

- Data layer: manages data access and storage

- Additional layers: cashing, logging, security, etc

An example here is a large e-commerce platform such as Amazon with separate services for user authentication, product catalog, shopping cart, and payment processing.

Server Infrastructure - From Metal to Cloud

As we have seen, a server is simply a computer and is thus made up of a CPU, RAM, storage, PSU, GPU, motherboard, and a few other components. Unlike our personal computers, server computers are designed to run continuously and sustain power over longer periods. For this reason, their components are designed at a much higher grade that makes them explosively expensive than our normal PCs.

The evolution from physical hardware to cloud-native deployments reflects decades of innovation in making computing resources more flexible, reliable, and cost-effective.

Bare metal, as the name suggests, is a physical server that sits in a data center somewhere, with each server serving just one tenant. This is beneficial because the tenant, have sole access can configure the server to their specifications. They also offer tenants high security, control and performance.

A cloud server, on the other hand, is basically somebody else’s bare metal server that has been virtualized. This came about due to the fact that businesses are now fast and companies need new servers within minutes, and bare metal servers take time to be set up. While an OS sits on top of a bare metal server, cloud servers have a hypervisor which create multiple virtual machines on a single server, by splitting the resources.

Physical Servers: The Foundation

Physical servers, often called “bare metal,” are actual computer hardware dedicated to server functions. It is called a bare metal because it’s a physical metal server that contains a client’s chosen configuration.

Generally, you need physical servers when you require

- Dedicated resources: All CPU, memory, and storage belong to your applications

- Predictable performance: No “noisy neighbors” competing for resources

- Complete control: Full access to hardware configuration and optimization

- High initial cost: Significant upfront investment in hardware

When Physical Servers Make Sense

- High-performance computing: Scientific simulations, financial trading systems Regulatory compliance: Industries requiring complete data control

- Specialized hardware: Applications needing GPUs, custom processors, or specific configurations

- Predictable, high-volume workloads: When resource needs are stable and well-understood

Real-world example: Netflix uses physical servers in their Content Delivery Network (CDN) because video streaming requires consistent, high-bandwidth performance that benefits from dedicated hardware.

Virtual Machines: Maximizing Hardware Efficiency

Virtual machines revolutionized server utilization by allowing multiple “virtual” servers to run on a single physical machine.

The Virtualization Layer

Think of virtualization like an apartment building:

Physical server is the building structure, the hypervisor = the building management system, while the virtual machines are the individual apartments. Resources, on the other hand are the utilities (electricity, water) shared among apartments

Key Benefits of VMs include;

- Resource efficiency: One physical server can host 10-50 VMs

- Isolation: Problems in one VM don’t affect others

- Flexibility: VMs can be created, resized, or destroyed quickly

- Disaster recovery: VM snapshots enable easy backups and restoration

Resource Management Virtual machines share physical resources through sophisticated allocation:

CPU scheduling: Time-slicing among VMs based on priorities Memory management: Dynamic allocation with overcommitment capabilities Storage virtualization: Shared storage pools with individual VM volumes Network virtualization: Virtual switches and VLANs for network isolation

Cloud Servers: Computing as a Service

Cloud computing abstracts away infrastructure management, allowing developers to focus on applications rather than hardware. They are virtualized servers that that run in the cloud on infrastructure owned by cloud service providers such as Fly.io, AWSEC2, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud Compute Engine, DigitalOceans, etc.

With cloud servers, you get a replica of the traditional physical server which you can spin anywhere in the world and host applications and compute workloads. These virtual spaces still run on physical servers owned by cloud service providers, who manage the underlying hardware and infrastructure.

While a bare-metal server occupies a physical space and requires electricity to run, a cloud server or VM is just a software that behaves the same way a physical machine.

Cloud servers operate based on virtualization, a process of creating and running a virtual instance of a real-life IT resource. Virtualization enables you to run difference OSs, workloads, and apps in multiple fully isolated virtual environments in a single physical machine instead of locking the entire hardware on a single OS and configuration environment.

There are different types cloud servers that an organization can choose from, they are categorized based on configuration and hosting type;

- General purpose; these offer a balanced ration of the resources (CPU, memory and storage) making them suitable for a wide range of applications like web servers and small scale databases.

- Compute-optimized; are designed for CPU-intensive workload, and provide a high ratio of CPU cores to memory and are ideal for compute-bound applications like batch-processing, scientific modelling, etc.

- Memory-optimized; these offer high RAM relative to CPU cores and hence are suitable for apps that require large dataset to be kept in memory like data analytics platforms and in-memory databases.

- Accelerated computing; these servers are equipped with hardware accelerators such as GPUs that offer special tasks such as graphics rendering

- Storage-optimized; they offer high disk throughput and are optimized for workloads that require high-speed access to large volumes of data

- High-performance-computing; these are cloud server instances customized for computationally intensive workloads that require high network performance and low latency

They can also be categorized depending on hosting types;

- Shared hosting

- Virtual private server hosting

- Dedicated hosting

Summary

This article introduces the client-server architecture as the fundamental computing model powering all modern digital interactions, where user devices (clients) communicate with powerful servers over networks to access data and services. It covers the core components including different client types (browsers, mobile apps, crawlers), various communication patterns (request-response, polling, WebSocket, pub-sub), and state management strategies across client-side, server-side, cache, and session layers. The post explains different architectural tiers from monolithic (1-tier) to complex N-tier systems, emphasizing the separation of concerns between presentation logic on clients and business logic on servers. Finally, it explores server infrastructure evolution from physical bare-metal servers to virtualized machines and cloud computing, highlighting how modern applications leverage different server types optimized for specific workloads and performance requirements.